When thinking of African exports, diamonds, coal, and even textiles may come to mind first – but what about animals?

We aren’t talking about poaching or illegal trade, but rather the sanctioned market of mammals in Africa sold both dead and alive for commercial and other purposes.

We used information from the CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) Trade Database to see how many mammals are being exported from Africa each year, what countries they are being imported into, which species are the most common in the trade, and what they’re used for.

We filtered our results for the mammals CITES lists as “threatened” to get a broader sense of how much legal, permitted trade is happening with species who are under threat of survival. Continue reading for a closer look at the legal trade of animals (and animal products) in Africa.

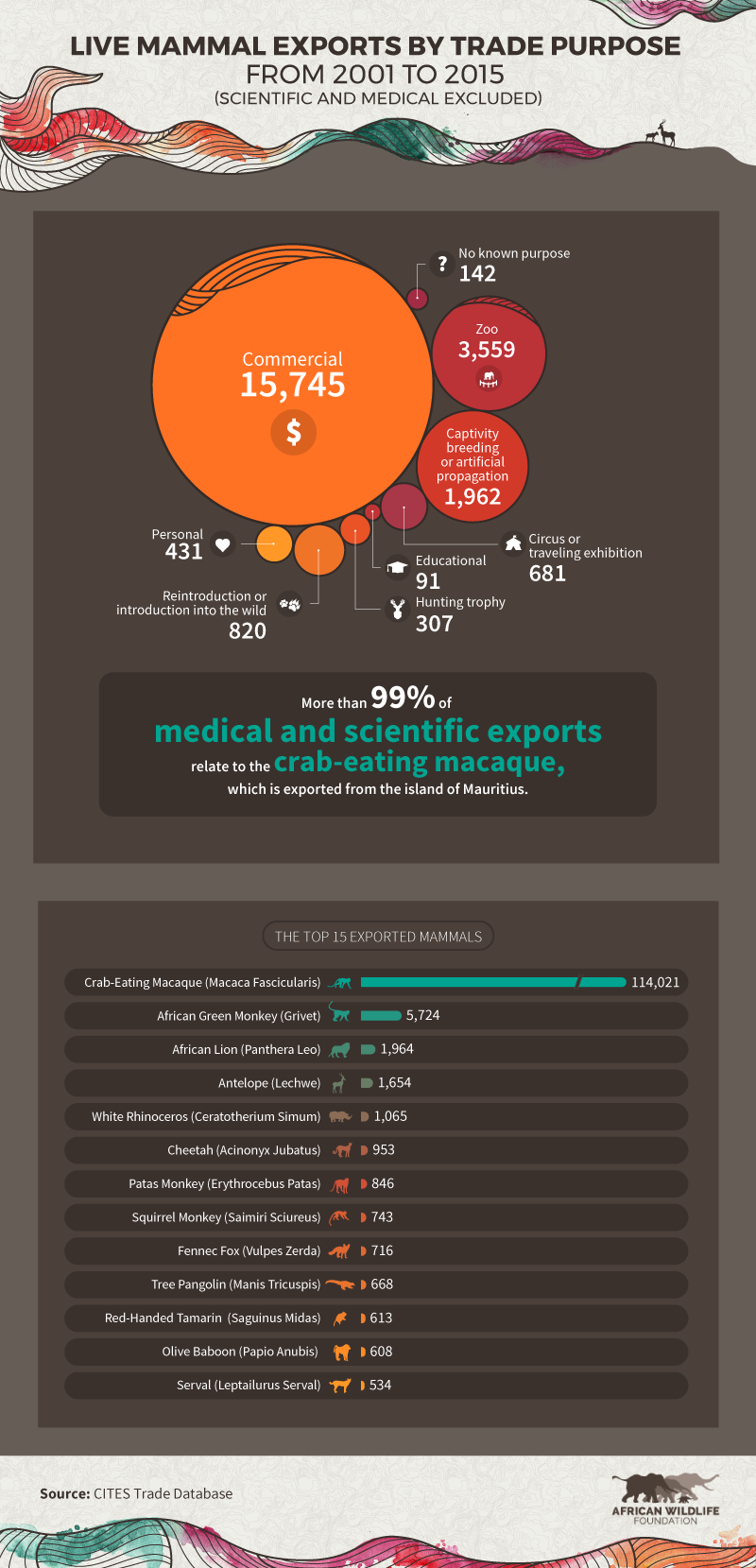

Our data showed that overwhelmingly, the live mammal trade (roughly 75%) consisted of trade categorized as for medical or scientific purposes. But that related almost exclusively massive amounts of shipments from the island of Mauritius of one single animal, the Crab-Eating Macaque. Because of this data skew, we considered only non-scientific and non-medical trading for the purposes of our research.

The Legal Animal Trade

The legal trade of animals and their byproducts represents a significant contribution to many African countries' economies.

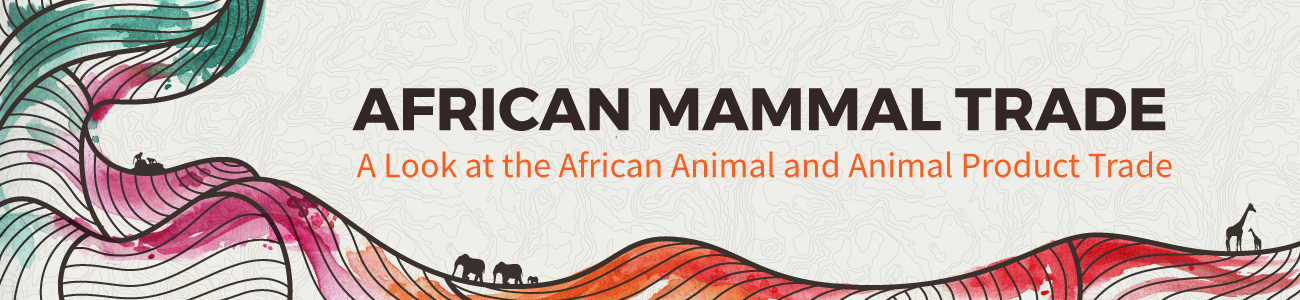

While African governments and countries legally support the importing and exporting of animals identified throughout this study, many of these mammals are also in danger of extinction. Our research shows discrepancies between the number of reported live animals sent from African nations and the number of animals received by recipient countries.

In some cases, the reported figures were different between exports and imports over a single year. In 2015, the number of reportedly received animals was approaching twice as many as the number of animals shipped. Similar results were found in 2014, where more than 3,000 animals or were reportedly exported, but more than 5,700 were received. In 2012, the inverse was recorded. More live animals were reported as sent than received, and we found similar results in 2007 and 2001.

These anomalies, though, are not entirely surprising. For instance, if two countries were permitted to exchange a certain number of animals, but fewer were shipped, differing figures could be reported based on who reported the transaction. But, to normalize the numbers, for the purposes of this study, we considered only Exporter Reported Quantities (that is, only shipments reported by African exporters).

Mammals Exported from Africa

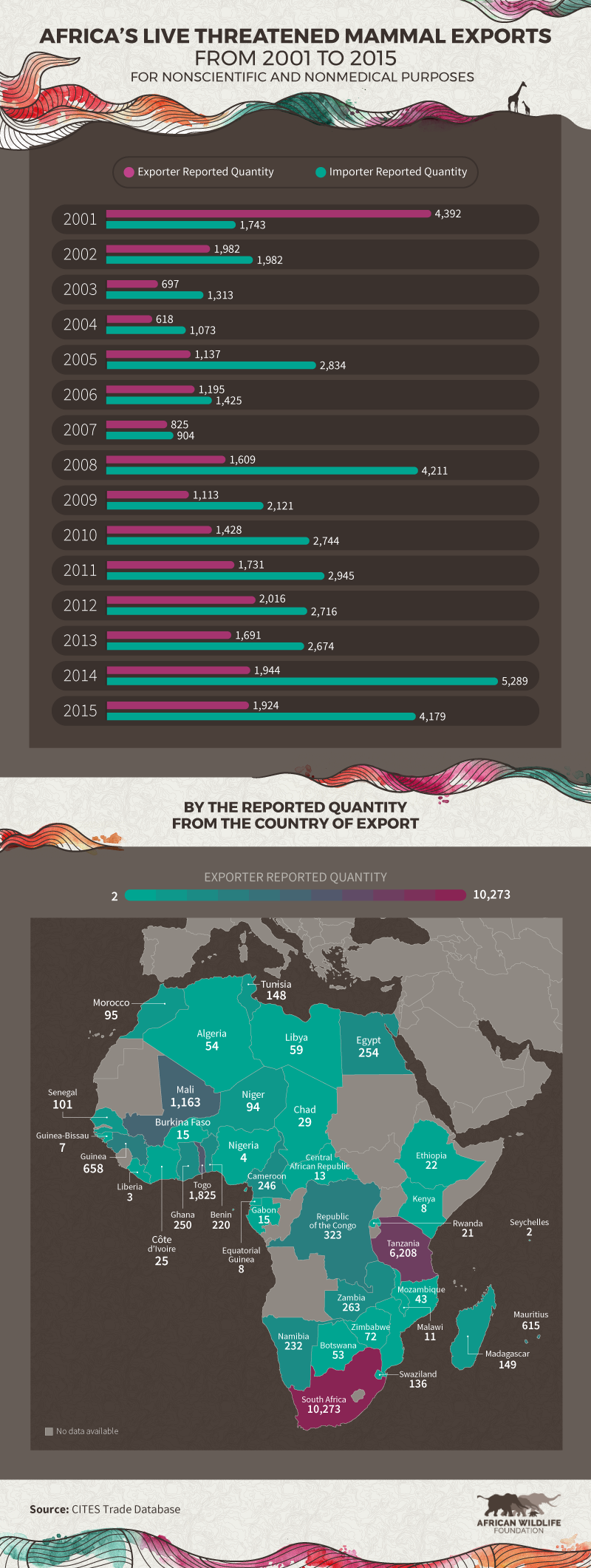

While the African lion was a common source of trade in many African countries, monkeys were the most commonly exported mammals between 2001 and 2015. Typically, these monkeys are exported as pets, which can result in higher volumes of captive breeding and animal abuse.

Other commonly exported mammals across Africa included the antelope, white rhinoceros, and cheetah. Both the white rhinoceros and cheetah are considered threatened and near-endangered species, with roughly 7,100 cheetahs remaining in the wild as of 2016.

Countries importing Africa's animals

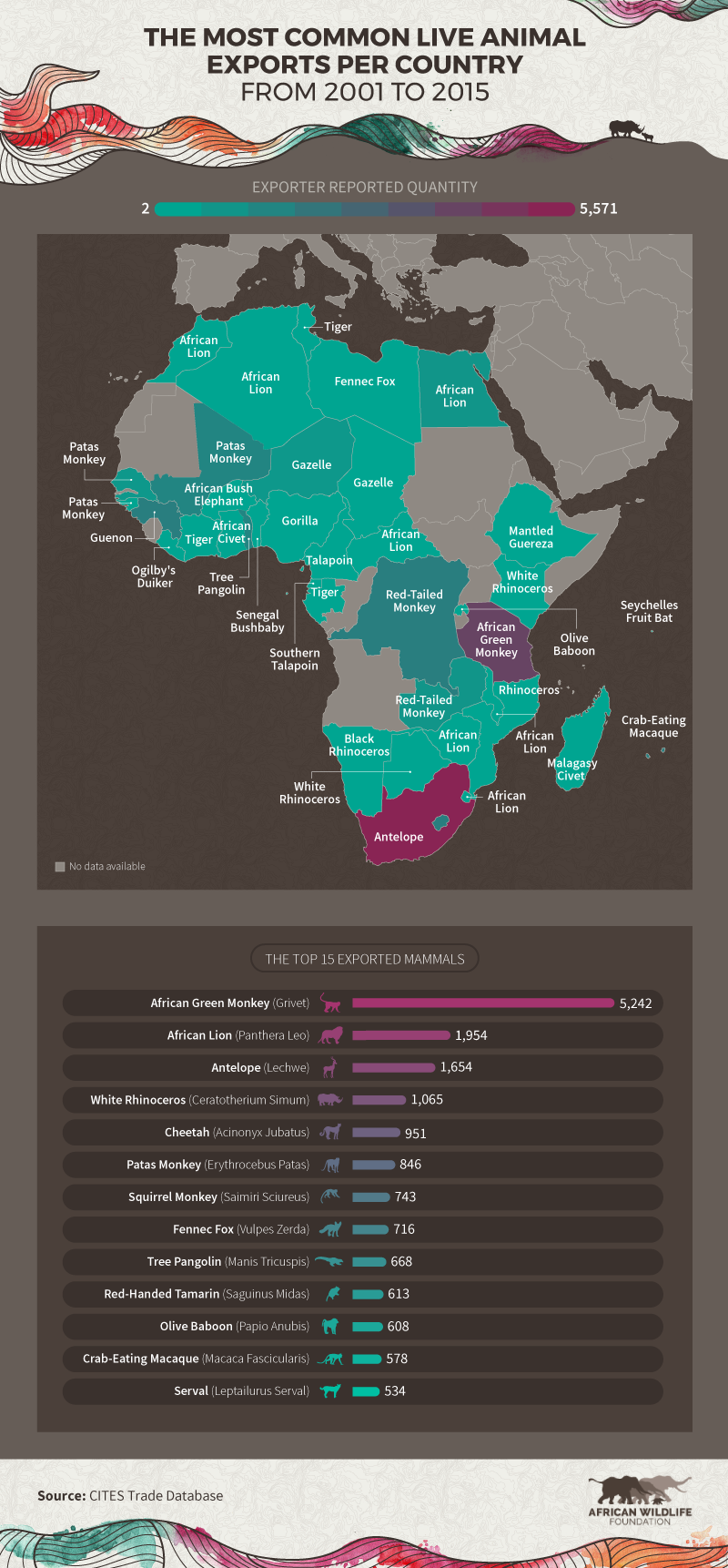

Of the nations accepting legal imports of live mammals, we found five countries with the highest volumes: Thailand, the U.S., Russia, China, and Namibia. For each of those, we identified their top three imports.

In the United States, the Crab-Eating Macaque, the same animal that makes up the majority of scientific and medical trade, was the most frequently-imported animal, though solely for commercial purposes. The Fennec Fox, a worldwide pet trend, ranked second in imports.

In Russia, the African green monkey was the most imported animal. Identified as a protected species by CITES, the two largest threats to the animal include hunting and captivity.

In Namibia, the antelope was the most commonly imported mammal from other African countries. In some cases (like the giant sable antelope), less than 100 of these endangered species remain and are in danger of extinction as a result of their role in big-game hunting.

The top reasons for the animal trade

While live mammals were exported from Africa between 2001 and 2015 for commercial purposes, a vast majority was traded for science and research. In fact, according to CITES, the crab-eating macaque accounts for 3 in 4 mammals exported from Africa and 99 percent of all research-related exports.

The crab-eating macaque originates from Southeast Asia and is an invasive species in South Africa. Considered one of the “world’s worst invasive alien species,” the crab-eating macaque may be responsible for the extinction of other forest birds in the Western Cape. As a result of the close physiology they share with humans, the crab-eating macaque is primarily used in scientific research and lab testing for medical experiments.

Beyond the medical and scientific realm, which we did not consider for this study, according to CITES data, more than 15,000 mammals were sold for commercial purposes, and more than 3,500 were exported to zoos.

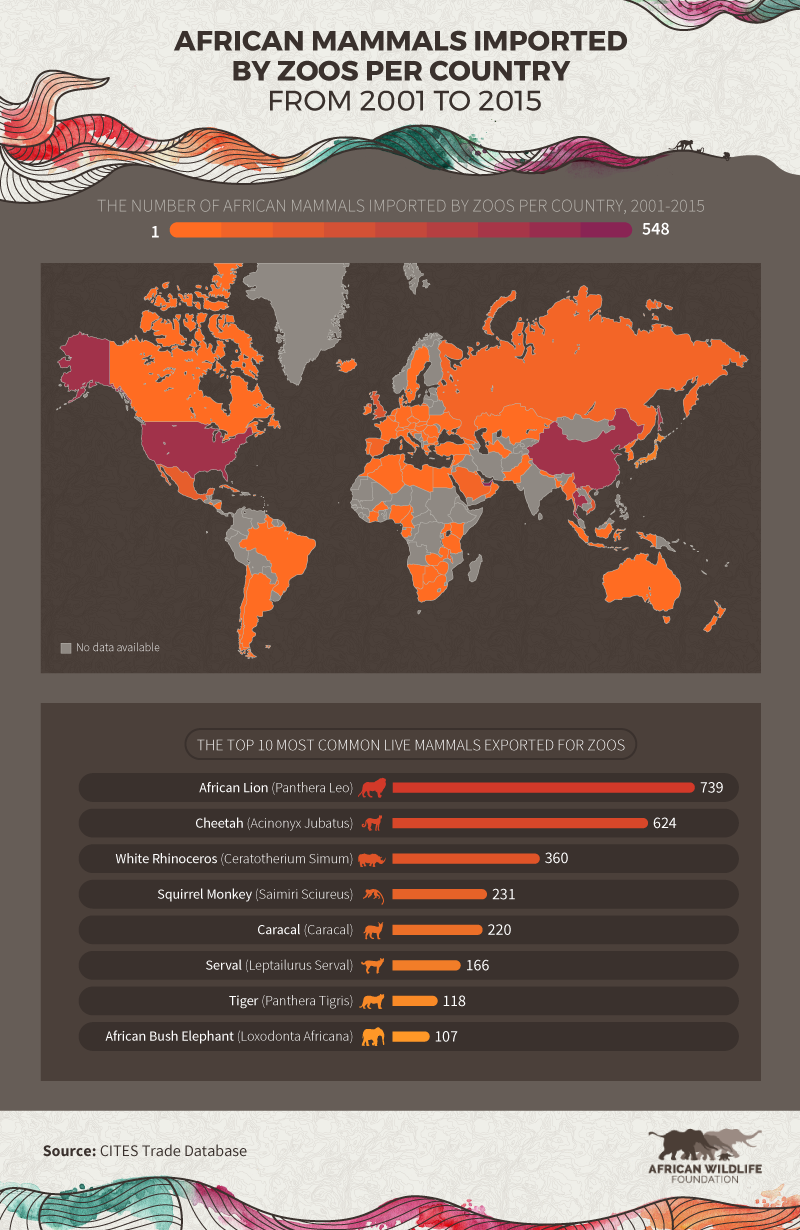

from the wild to the zoo

While the export of live mammals from Africa to zoos around the world only represents a small fraction of the total industry between 2001 and 2015, it still reveals information about the importing of thousands of animals, including many of the most familiar. Our study of CITES data revealed that the United Arab Emirates (548 animals), Thailand (424), and the United States (400) were the largest importers of live mammals for zoos, and the bulk of their trade came from South Africa.

The African lion was the most commonly exported mammal with “Zoo” as the described purpose by CITES, over the 14-year span we studied, followed by the cheetah and white rhino. While the typical lifespan of an African lion in the wild is between 14 and 16 years, lions in captivity may live up to 30.

Hunting Africa's threatened species for sport

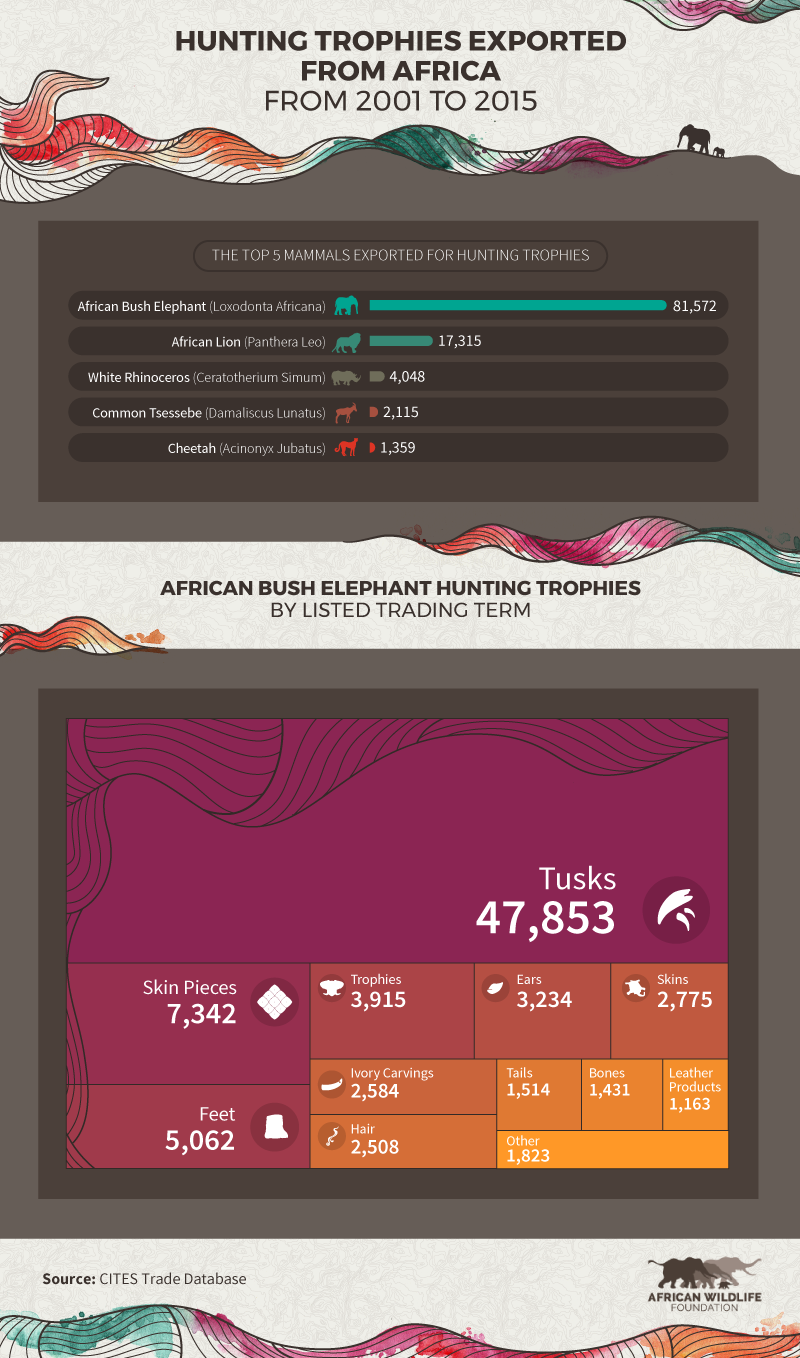

When you think of elephant tusks and lion pelts being exported as hunting trophies out of Africa, your first thought may be illegal poaching and black markets that often make headlines. In reality, many African countries allow the legal hunting of these threatened or endangered animals (to an extent) and the exporting of their byproducts as trophies.

According to CITES data, the African bush elephant accounted for roughly 4 in 5 animals whose parts were exported as trophies between 2001 and 2015.Elephants aren’t the only animals affected by the hunting and trophy trade. More than 17,000 African lions were killed, and their pelts, heads, and bones were exported as trophies in the same 14-year span.

Other mammals hunted for sport and then exported as trophies include the white rhinoceros (more than 4,000), common tsessebe (2,115), and cheetah (nearly 1,400).

bridging the gap

While the importing and exporting of African mammals detailed here represents legal methods of trade, for the hundreds of species of mammals that call Africa home, the reality of their status as an industry can be much more complex. Some species, including elephants, rhinos, and lions, have experienced rapid, unsustainable declines in their population sizes due to the cumulative effects of human-induced mortality, defined by such threats as habitat loss, poaching, human encroachment on wildlife areas, human-wildlife conflict, and legally-sanctioned offtake activities such as sport-hunting. For those species, it is necessary to scale back any human activities that may result in a further decline in their populations.

The threatened species of wildlife in Africa need your help. At the African Wildlife Foundation, we believe protecting African wildlife means empowering local communities and people through jobs, education, and conservation training. Many species across Africa face extinction, and their survival depends on bridging the gap between mankind and the lions, elephants, and rhinos we share the earth with. To learn more and how you can help, visit us online at AWF.org today.

Methodology

The data for this project was pulled from the CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) Trade Database.

We pulled data for all animal exports from 2001 to 2015 (the latest full data are available) and included only Appendices I and II species: Those that are threatened with extinction or may be threatened unless action is taken (more info: https://cites.org/eng/app/index.php). For all graphics, except where noted, we looked solely at exporter reported quantities (the number that African exporters are reporting they send) rather than importer reported quantities (the quantities importers say they received from African countries). We looked at mammals for the purposes of this research. What we found is that almost 75% of all trade from Africa related to a single animal, the crab-eating macaque, exported from a single country (Mauritius) that was listed as being exported for scientific or medical purposes.

For the purposes of this project, we excluded transactions related to scientific and medical purposes to normalize the data. We also excluded the common marmoset from our data, which is not endemic to African countries. Note that the CITES database only represents legal, permitted trade of these animals and animal parts and does not show black market or illegal trading of protected species.

Sources

- CITES trade statistics derived from the CITES Trade Database, UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK.

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/05/which-are-africas-biggest-exports/

- http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/zaf/#Exports

- https://phys.org/news/2017-06-south-africa-export-lion-skeletons.html

- https://mg.co.za/article/2017-07-19-south-africas-lion-trade-endangers-big-cats-abroad

- http://www.enca.com/south-africa/sas-problem-with-exporting-small-monkeys

- http://rhinos.org/species/white-rhino/

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/12/cheetahs-extinction-endangered-africa-iucn-animals-science/

- http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-zootopia-foxes-china-20160330-story.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/feb/26/social-media-helps-fuel-chinas-illegal-craze-for-thumb-monkeys

- https://www.ewt.org.za/WILDLIFETRADE/info/FAQ%20Exotic%20Wild%20Animal%20Pets.pdf

- http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/factsheets/entry/vervet/cons

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150521-angola-giant-sable-antelope-operation-noahs-ark-south-africa/

- http://www.invasives.org.za/legislation/item/848-crab-eating-macaque-macaca-fascicularis

- https://www.thainationalparks.com/species/crab-eating-macaque

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/11/151119-elephants-zoos-Swaziland-import-conservation-rhinos/

- https://qz.com/586299/zimbabwe-plans-to-export-more-baby-elephants-to-china/

- http://www.marylandzoo.org/2010/09/animal-questions-from-base-camp-discovery-how-long-can-a-lion-live/

- http://www.marylandzoo.org/2010/09/animal-questions-from-base-camp-discovery-how-long-can-a-lion-live/

- https://conservationaction.co.za/resources/reports/cites-elephant-trophy-hunting-quotas-2017-1188-african-elephants-may-legally-hunted-2017/

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/11/151715-conservation-trophy-hunting-elephants-tusks-poaching-zimbabwe-namibia/

- https://mg.co.za/article/2017-07-19-south-africas-lion-trade-endangers-big-cats-abroad

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/07/150722-lions-canned-hunting-lion-bone-trade-south-africa-blood-lions-ian-michler/

- https://www.awf.org/

- https://cites.org/eng/app/index.php

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/07/150722-lions-canned-hunting-lion-bone-trade-south-africa-blood-lions-ian-michler/

Fair Use Statement

The more knowledge we can gain about the state of wildlife in Africa, the more we can do to help. If you found this article informative, please share for noncommercial purposes only. Please link back to this page to give the original authors credit for their work.